Green Space and Grassroots: London’s Parks and the Origins of Football

Visit our website for more info!

With the Euros well and truly underway and England for once making a decent account of themselves, we thought we would explore the key role London has played in the history of football. Of course, we’ve all heard of Arsenal, Chelsea and Tottenham, who occupy the big three positions in the city’s football ecosystem today and have won numerous national and international trophies between them—well… maybe not Spurs—but what else has London contributed to the development of English football?

Football has long been London’s most popular sport, and the city has historically been well-endowed with open space (as we’ve spoken about previously) and, for a time, purpose-built football pitches for anyone to use for a kickabout. But seeking them out is becoming increasingly difficult and the facilities that grassroots teams have relied upon for many decades are falling into disrepair thanks to dwindling municipal investment. At Walulel we understand the importance of having leisure space for sport and relaxation, and perhaps shining a light on how London’s very own open spaces have contributed to the development of the sport will help others see its vital historical and future role in the country’s wellbeing!

It’s likely that some form of football has been played in the capital for as long as both have existed, but the first record of it being discussed dates all the way back to the 1170s when the cleric and clerk of Thomas Becket, William FitzStephen, wrote of London’s youths rushing out to the fields to play ‘a ball game’ after their Shrove Tuesday lunch. Even a millennium ago it wasn’t uncommon for kids to have a kickabout in whatever green space they could find!

Numerous references were made to the activity throughout the middle ages, not least when monarchs attempted to ban it, and this happened a lot. Edward II issued a proclamation in 1314 stating the noise caused by ball games was evil and forbade them ‘on pain of imprisonment’, and his father Edward III followed with his own decree in 1349. The ball game was first described as “football” in 1409 when Henry IV, concerned with levying of money from ‘foteball’, outlawed the game and imposed a fine of 20 shillings for anyone found playing.

Edward IV also forbade “football and such games” deciding that it was a distraction for able bodied men from practicing archery. Even Henry VIII, despite having had the first recorded pair of football boots specially made by his cordwainer, attempted to prohibit the game in 1540.

Given the sheer number of banning orders it is clear than no attempt was fully successful, though it seems as though football was seen as an unrefined sport played by the lower classes. In King Lear, Shakespeare described those who practiced it as ‘base’ and spoke poorly of it in A Comedy of Errors. This was in spite of the fact that in 1618 James I instructed good Christians to play every Sunday afternoon after worship to demonstrate that Protestantism didn’t have to be as Puritan as the Puritans were making it out to be.

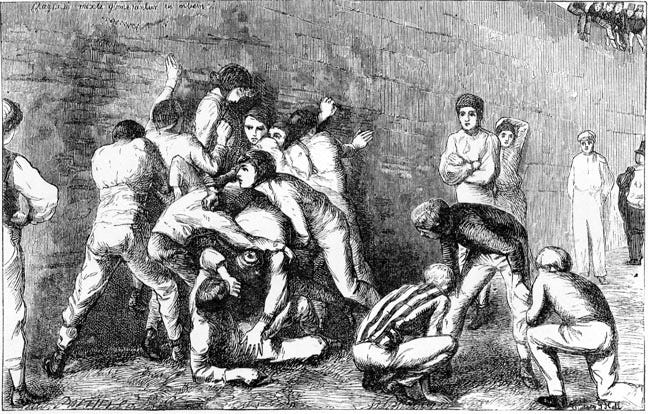

There’s no doubt though that the football of the time was brutal and unruly, and outside of the universities and schools of the day it would have been played predominantly by working people. This “mob” or “folk” football would often fill the streets and fields of London on the days of county fairs with teams made up of hundreds of players attempting to herd one or several balls into a goal over a mile away, inciting riots and breaking bones and windows alike. These destructive results were what one sixteenth-century Scottish poet called ‘the beauties of football’.

Richard Mulcaster, headmaster of St Paul’s School on the banks of the Thames in Barnes, is credited with formalising the game and introducing referees in his 1581 writings. Public schools had long adopted football as a “character-building” sport that later coincided with a Victorian “Muscular Christianity” and supposedly toughened up their pupils.

Harrow School in north-west London, along with St Paul’s, Westminster and the country’s other public schools, helped transform it into a more refined sport up until the mid-19th century in order to compete in games between one another. By this point much of the land that had previously been available to practice sport and glean crops had been enclosed and only those who owned or could afford to pay for access to private land had the chance to play.

There were still no official rules though, until number of wealthy amateur teams with public school roots emerged in the 19th century. In 1863 representatives from eleven of these teams from across London, from Barnes, Chiswick, Epping Forest, Kilburn, Crystal Palace, Blackheath, Kensington and Surbiton all met at the Freemason’s Tavern in Covent Garden to establish the official laws of the game. Barnes’s own Ebenezer Cobb Morley had proposed the formation of a governing body for football that year and founded what became known as the Football Association (FA). The first FA recognised match was between Barnes and Richmond in December that year, fought out in a public park called Limes Field.

The inaugural FA Cup was contested across London’s green spaces in 1871-72, with its final, between Epping Forest’s Wanderers FC (who played mostly in Battersea Park) and the Royal Engineers, at the Kennington Oval cricket ground in front of 2,000 spectators. Though this match, and the cup as a whole, was an upper-class affair, comparable to Henley or Royal Ascot, at the same time London’s industrialisation was depriving the working class of rural pastimes, forcing them to seek out urban leisure. The reclamation of once-enclosed green spaces for “People’s Parks” in the mid-to-late-19th century gave workers, who had successfully fought for Saturday afternoons off work (which is why today Saturday matches still kick off at 3pm), the space and time to turn their hands—or feet—to football.

Young men and women organised themselves into teams representing their own trade union, workplace, church or pub and such “works” teams were founded, initially using their local park or playing fields as a pitch. Of the remaining professional men’s teams, Millwall emerged in 1885 out of workers at the JT Morton canning factory on the Isle of Dogs and played on the converted marshland of Millwall Park, and Arsenal was formed from munitions workers at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich in 1886, with Plumstead Common their home pitch, and were the first London team to reach the First Division. Thames Ironworks FC followed suit in 1895, playing at Hermit Road Recreation Ground, changing their name to West Ham United in 1900.

Meanwhile teams such as Fulham (1879) and Tottenham Hotspur (1882) were formed from local church schools, Leyton Orient (1881) and Brentford (1889) out of cricket clubs who cottoned onto football’s appeal, Charlton Athletic (1905) from a bunch of teenagers who all lived on the same street and played in the same park, and Chelsea (1905) from a millionaire’s failed attempt to sell the athletics track he’d bought and a severe dog bite.

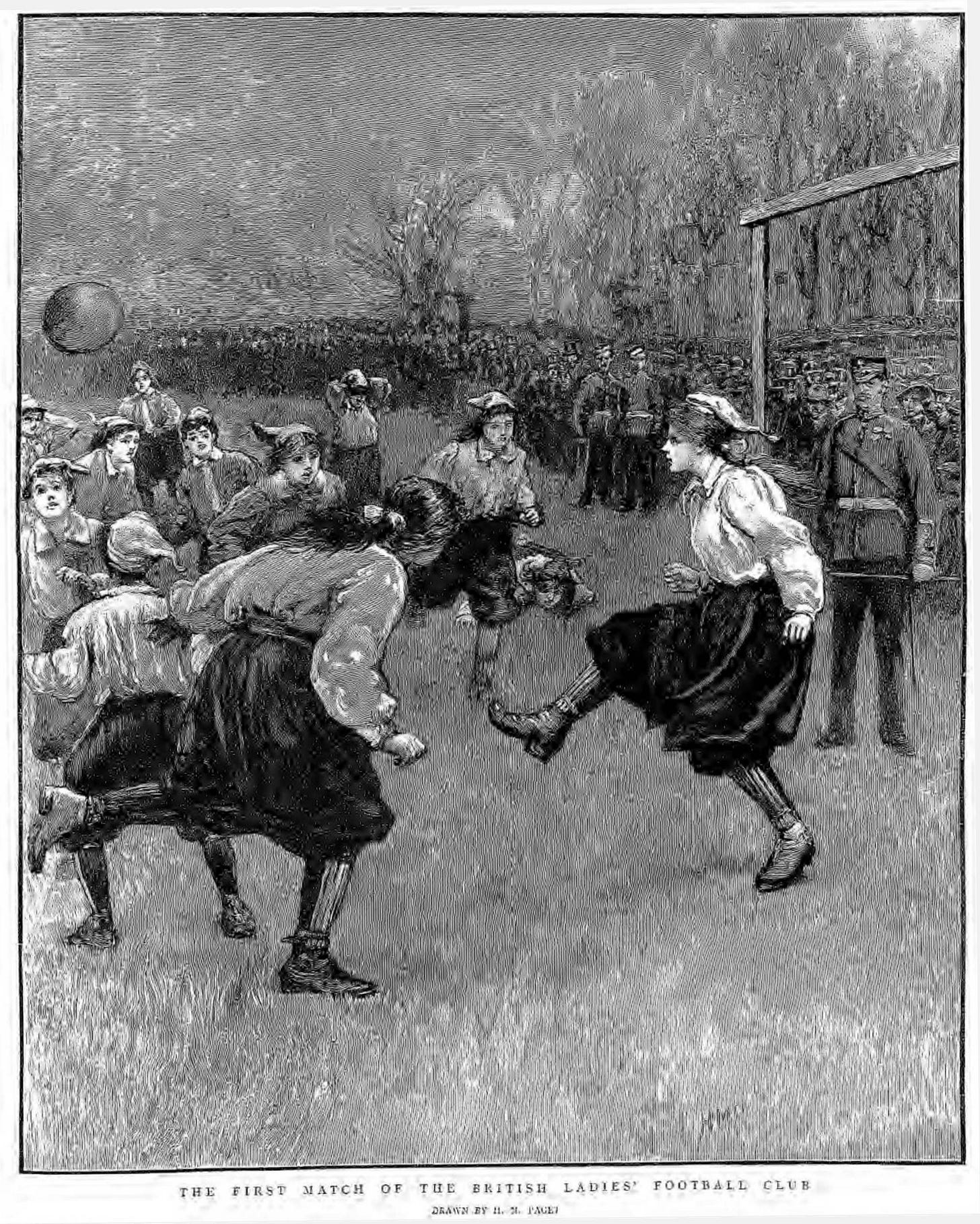

The British Ladies’ Football Club was also founded in 1895 under the patronage of Lady Florence Dixie, offering a chance for women who were interested in playing at a higher level to join a more elite team. They played their first match in Crouch End, with a teams representing the north and south of the country respectively in front of a crown of 10,000 spectators!

London’s rapidly improving public transport system, which we discussed in our previous two articles, allowed spectators and players, free from their Saturday afternoon shift, to travel to matches across the city and by 1905 average attendance was almost 15,000. The rising popularity in the late-19th century led many clubs to start charging entry fees to develop facilities and cover the wages of working players who were missing out on other work, and as insurance against injury which would have made both football and a return to manual labour impossible.

Clubs quickly became professional ventures and limited liability companies, mainly for the purpose of buying land for stadium facilities, many of which were designed by Scottish architect Archibald Leitch (1869-1939). These stadia, such as Craven Cottage and Stamford Bridge, moved supporters from the local playing fields to purpose built amenities that enabled upwards of 100,000 to witness the country’s new favourite pastime.

By 1910 there was 12,000 FA-affiliated clubs across the country, and over the 20th century, despite football becoming professionalised, it remained the ‘most important social activity’ for many thousands of Londoners. That wasn’t just for those who went to watch matches or followed a team, but because, outside of the increasingly organised league system, football on the whole remained a fairly disorganised community-based hobby that took place in fields and recreation grounds, streets and courtyards, in the same way it had done for hundreds of years. This manifested itself both in kickabouts in the park and amateur leagues that included many popular tournaments for women.

The amateurism that football had been founded on was embraced across the country and London was no exception. Sunday league football emerged when the city’s dock workers, who still had to work on Saturday afternoons, decided to form teams to compete on Sundays despite its observation across the country as a day of rest. Traditional Saturday-playing teams who fielded players who also competed on Sundays could face harsh punishments, such as Tooting and Mitcham Utd who were expelled from the FA Amateur League in 1925. It wasn’t until 1932 that a National Sunday League Association was founded, with 13 Sunday leagues in London joining up.

In 1947, as the dust settled following the Second World War, the rubble from bombed out houses in east London was smoothed out to create the foundations for the vast Hackney Marshes, on top of which turf was laid to create over 120 football pitches. The Hackney and Leyton Sunday League was founded there that year and combined with the existing Sunday League Association, and hundreds of games continue to be played there each week. By 1960, Sunday league football was a phenomenon throughout the country by over 500,000 players. Men’s and women’s amateur football grew greatly in popularity over the next couple of decades but from the 1980s onwards the amateur game took a sharp decline.

This was for a number of reasons, but it mainly comes down to a lack of funds for football facilities. Despite the incredible money involved in the sport today, with hundreds of thousands of pounds a week paid to individual players, or billions of pounds worth of TV deals going to the top leagues, there has never been very much that has ended up in the coffers of the amateur leagues, despite their FA affiliation.

As Local Authorities have been predominantly responsible for the upkeep of park pitches, their reduction in funding over the decades has led to a decline in groundskeeper staff. Combined with country’s unpredictable weather, made extra apparent by the past month’s unprecedented rainfall, that has made underfunded and thus poorly maintained pitches unplayable. Councils have also gone on to raised pitch fees to cover the shortfall when teams understandably wish to play elsewhere, or, sadly, stop playing altogether.

Since 2000, though, London has received £235m from the Football Foundation which has been spent on more than 3,500 community projects including 400 grass pitches and 71 changing facilities. The city’s major clubs also run initiatives to encourage grassroots sport, and recently the FA has made a commitment to invest £230m in artificial pitches and 150 football hubs in 30 cities as part of its 2020 vision. The Premier League has also donated £1bn to grassroots sport but it is unknown whether this and all the other investments will make a difference after such a long period of chronic underfunding, or if it will be able to reverse the downward trend in grassroots participation.

It has long been known how valuable local green spaces and pitches are to the formation of community driven by participation in football at all levels. Their existent and maintenance offer amateur players not only space to enjoy their pastime but a springboard to greatness, too, with the likes of Ian Wright beginning his career in a Bermondsey Sunday League team. Competition all the way up the pyramid is what has spurred English football to be a potential world beater, and without it there’s little chance the England team would be where it is today.

Recently, the Museum of London, in partnership with the GLA released a film titled ELEVEN in June 2021, documenting eleven London grassroots football stories and its importance throughout the city’s history. It features walking football for the over-50s; Benjamin Odeje, the first black footballer to represent England; a team exclusively for women and non-binary players; amputee football; youth projects; Grenfell Athletic; and even a Piccadilly vs District line workers rivalry. The film demonstrates how necessary grassroots football is to build communities and challenge adversity, and highlights how ingrained the amateur game is in the psyche of London.

Clearly there is a desire for people to play football—there always has been—but we need somewhere to play it. As lockdown has shown, green spaces are imperative to the physical and mental health of a community and only by maintaining and investing in our local parks and playing fields can we continue London’s proud footballing history.