A potted history of London's green spaces

How the 'Big Smoke' became the world's first National Park City

Green spaces have for centuries been an important feature of the urban landscape, providing an escape from the dirt and bustle of the city environment while also existing as a constituent part of it. During the Covid-19 pandemic, however, parks, greens, gardens, churchyards, commons, marshes, meadows, squares and woodlands have come into their own as spaces to socialise, exercise or simply get out of the house.

Even as the temperature has dropped and the nights have drawn in, they have become more versatile than ever; the classroom, the pub, the dancefloor, the date venue – all speedily fashioned out of the humble green. The crisis has emphasised the virtues of these urban oases, and for that reason we believe it is an important time to delve into the significant history of the UK’s urban green spaces, in order to underline their necessity going forward.

One Tree Hill, Honour Oak, outerlimitslondon

Visit our website for more info!

We’ve long known that access to green space does wonders for the mental and physical health of city dwellers, but during the warmer months of lockdown, local parks became the country’s second home. With the pubs, cafes and gyms shut it was practically the only place anyone could socialise or exercise. Even now approaching winter, local parks still provide countless urban dwellers with somewhere to catch the last rays of afternoon sun, meet with a friend or go for a jog.

Despite its ‘Big Smoke’ reputation, London is no different, and in fact its residents are some of the luckiest when it comes to public open space. 33% of Greater London’s land is taken up by it, which enabled the capital to become the first National Park City in 2019.

Yet how did events conspire to mean that London, a city whose history, as we’ve seen in previous articles, has been dominated by industrialisation, overcrowding and pollution, end up in the world’s top 10 green cities? Was it in fact these very crises of modern urban life that helped spur London on in its path to greenness? We shall see.

But, because we can, let’s start in Ancient Rome.

The modern portrayal of Ancient Rome as pristine, white and wholly urban make it hard to imagine that Roman city dwellers had a strong affinity with the rural. Though even back then, the Romans understood that being cut off from the countryside led to stress, dehumanisation, and alienation from natural forces.

Gardens were highly valued amongst all strata of society. Lower class families used their own private plots for growing herbs and vegetables and rearing livestock, as well as considering them decorative, adorning them with an abundance of ornamental trees and brightly coloured flowers.

Public parks and pleasure gardens featuring cultivated foliage, fine sculpture, temples and water features were common too. The Gardens of Sallust were specifically bought by Emperor Tiberius as a public amenity and maintained by subsequent leaders for centuries – just one of many examples of a leisure space deployed for the benefit of the demos.

19th century engraving of the Gardens of Sallust, lookandlearn.com

Wealthy Romans also established their own ‘horti’, lavish villas set within landscaped parkland, with Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea standing out as the most impressive. Estimated to have been between 100 and 300 acres, the site contained artificial lakes and marshes, groves, pastures, vineyards, colossal sculptures, aqueducts and other works of monumental architecture. It was in reference to the Domus Aurea that Suetonius coined his famous term ‘rus in urbe’, or ‘country in the city’.

Finding balance in the relationship between the rus and the urb has always been crucial in the maintenance and expression of power. Ensuring your population had access to this life-affirming quality was key, but so was the ability to cultivate and distribute resources including food and raw materials.

Throughout the turbulent medieval period in England, rulers put emphasis on the symbiosis between the cathedral city and its surrounding hinterland in order to keep the population relatively compliant as new regimes came to power.

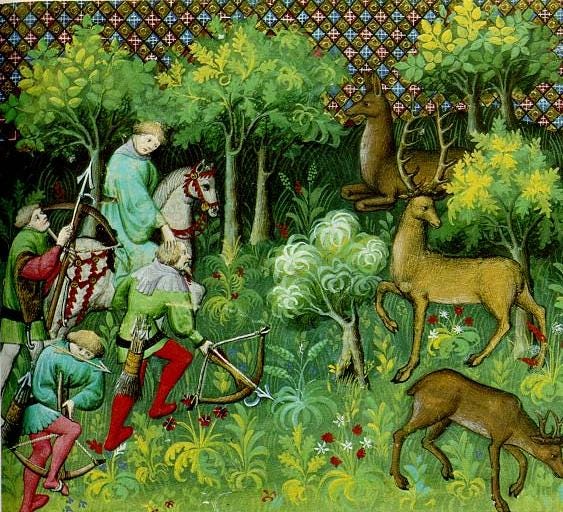

Common lands were written into statute in 1235, though they were already well established informally. These allowed anyone to farm or graze their livestock on land that was held by the landowner (often the church or aristocracy) and survive off the goods that the natural world provided them – living and making a living. The number of animals and time of year when rights could be exercised were controlled by local leaders to ensure resources would remain plentiful. The Lord of the Manor was also strictly advised to leave enough of nature’s resources so that all commoners could continue to glean what was needed.

Medieval citizens hunting on common land, wikiwand

Any large-scale building tended to be contained within city walls, the 13th century foundations of Parliament allowing for collaboration and alliances between landowners inside and outside these urban borders in a manner unique to the UK and London in particular. Such relationships allowed London to expand through the absorption of faraway settlements into the wider administrative whole, including the vast swathes of greenery that sat between the city and town. Roads were built to connect the two and hamlets developed along them amidst the greenery.

Many of the greens that were cultivated between nearby towns played important roles in history as battle grounds or meeting points for movements such as Watt Tyler’s Peasants’ Revolt, who rallied on Blackheath in 1381 before they entered the city and sacked the Savoy Palace.

Royal hunting and leisure parks such as Richmond and St James Park became more established but continued to give citizens access to open space and resources. In 1618 one of the country’s first purpose built public spaces began its development in the form of a Commission on Buildings for Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The public square was laid out in the 1630s on the former Holborn grasslands for the sole purpose of leisure – grazing livestock was removed so that turnstiles no longer had to be used to prevent cattle escaping.

1682 map of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Friends of Lincoln’s Inn Fields

Building licences were only granted for houses surrounding the square as long as it remained open to the public for the “pleasure and freshness for the health and recreation of the Inhabitants thereabout”, so wrote the commission. The gigantic Hyde Park, one of Henry VIII’s hunting grounds was opened to the commons soon after in 1637, and many other public squares followed in the interest of providing everyday citizens with access to life-giving open space.

Not long after, though, laws of enclosure were passed throughout the country restricting access to a huge amount of England’s once public space. These had been enacted on a small scale for centuries with local authorities extending rights of landowners and supporting their privatisation of land. But these became more and more formalised in the 18th century. St James’ Square, for example, was enclosed in 1726 by an Act of Parliament, reserving access to the wealthy homeowners who lived around it.

In 1751, Princess Amelia attempted to enclose Richmond Park from all but a few close friends. This lasted until 1758, when local brewer John Lewis took the gatekeeper to court and won!

The Inclosure Act of 1773 pretty much put an end to the communal use of land in the interest of landowner profits. As a result of 5,200 enclosure acts, this one being the most extensive, more than 6.8 million acres of former commons were privatised by 1914. Many people’s access to food and natural resources were removed leading to a number of violent conflicts and an extremely controversial legacy even to this day.

Hyde Park on a Sunday, 1804, reserved for the upper classes, British History Online

The march of industrialisation further drove the wedge between rus and urb with a dramatic rise in pollution, squalor and steam-powered machinery – Dark Satanic Mills sat in sharp contrast to England’s green and pleasant land. Overcrowding increased as people flowed to the cities for work and much of the open space was replaced much-needed housing or new factories.

Only the vast but sparsely positioned royal lands, private fields on the outskirts of town belonging to farmers, and squares accessible only to the wealthy remained, and millions were left without access to greenery. Disease was on the rise, and in the interest of public health something had to change.

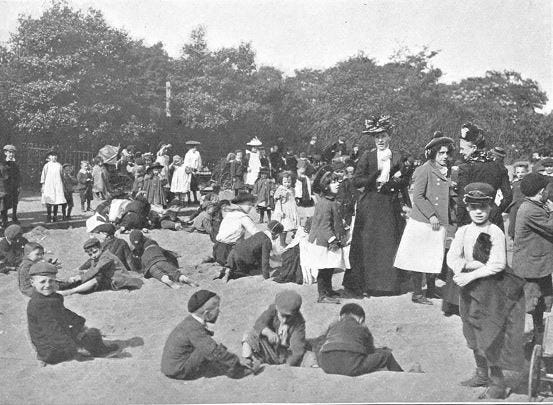

Some private parks were opened to the public on a temporary basis. Regent’s Park for example was redesigned and opened for 2 days a week in 1835, which slowly expanded over the decades to every day. Victoria Park in Tower Hamlets was the capital’s first purpose built ‘people’s park’, opened in 1845 after a mass petition to the Queen after a recommendation from epidemiologist William Farr, on the grounds that Londoners were in desperate need of fresh air. The park provided working families with bathing and swimming facilities, and for many was the first swathe of uninterrupted greenery they’d ever seen. In the 70s and 80s the park hosted music festivals such as Rock Against Racism.

Victoria Park Sandpit, 1901, Encyclopaedia of Victorian London

Victoria Park was soon followed by Crystal Palace Park, which became a leisure ground following the Great Exhibition of 1851. Kennington Park was opened in 1854, Battersea Park in 1858 (though its local power station was soon to become a symbol of polluted London), and Finsbury Park in 1869, with many more coming soon after.

These green public spaces offered working people clean and healthy outdoor facilities and actively improved the health and wellbeing of millions of citizens, allowing them to escape what was believed to be disease-spreading miasma of the polluted inner city. Ever since, Londoners, and by extension Brits, have developed a deep cultural affection with and expectation of access to local parks. That said, there were many areas that remained isolated from easily accessible public greenery.

By the turn of the century, influential public intellectuals were loudly making the case for the green city. William Morris wished for ‘the town to be impregnated with the beauty of the country’, while Ebenezer Howard proclaimed that the ‘Town and country must be married’.

But despite the strides made with public parks, the rush outwards to escape the metropolis from the mid-19th to mid-20th century took the government’s attention away from greening the inner city. Building homes in the suburbs for returning soldiers from both wars and those left homeless by bombing raids became a necessary priority leaving the centre, as mentioned in previous articles, to the factory and later the office block.

The social changes following the Second World War did however mean that the government started really thinking about healthier cities. The post-war years saw the emergence of the NHS, National Parks, the Town and Country Planning Act and the Green Belt, all of which sought to further protect the constitution of the British public. That said, coal burning factories remained in the city and the mass-produced motorcar became all the rage. Combined with adverse weather conditions, these polluters helped cause the disastrous Great Smog of 1952 in London, which in turn helped lead to the Clean Air Act of 1956.

But as deindustrialisation advanced into the late-20th century and more rigorous medical research was undertaken into the significant mental health benefits of open-air leisure space, attitudes towards the genuine integration of greenery into the urban environment changed. The preservation of natural capital became order of the day.

The former industrial plots of land that weren’t converted into offices or housing were left open for pocket parks or public sports courts, and the canals became more a scene of bucolic serenity than heavy industry and horse dung that they were the decades previous. Urban walks became fashionable with the opening of routes like the Parkland Walk in 1984 and the Green London Way in 1991, and more recently the Capital Ring in 2005 and Jubilee Greenway in 2012.

Parkland Walk, Haringey, londonist.com

Though, despite the fantastic advances that the city has seen in its ability to offer its citizens access to open space, as London becomes greener, it is also growing, leaving many stuck without local parks. The coronavirus pandemic has shown us more than ever the importance of one’s location relative to public green space while other local amenities remain closed. The closure of some parks due to overcrowding has also highlighted how desperately in need many people are for their own local green spaces to prevent long travels to those further away.

It is therefore crucial that renters, buyers, landlords, developers and councils all have access to the key data surrounding urban green space. An understanding of who is in need of such amenities has always determined the way cities are designed and how successful new developments or sales/rentals will be. But seeing how history has shaped the way citizens perceive and appreciate the natural world around them, and looking at the changes that the pandemic has made to peoples’ desire to be closely positioned to outdoor space (not to mention the huge impact of climate change, which this article was too short to discuss) are likely to force these green considerations to the top of the pile in all urban aspects. Only then can we begin to create a truly healthy city that can stand up to a crisis such as this one and others that may arise in the future.