The history and value of hotels in London

Visit our website for more info!

“The great advantage of a hotel is that it is a refuge from home life” - George Bernard Shaw

Few industries define London more so than that of tourism. As one of the most popular destinations in the world, the city attracted almost 21 million visitors from overseas in 2018, as well as hundreds of millions of day-trippers, bringing in over 11.5% of the capital’s GDP and providing 700,000 jobs to its inhabitants. While its the attractions such as the London Eye, the British Museum and Big Ben that get the headlines, often overlooked are the places people stay - the hotels, the hostels and the b&b’s, that provide the city’s tourists with a roof over their head and a bed for the night. It certainly remains the case that without proper hotel facilities even the most attractive city would be unable to develop into a major tourist centre.

With the arrival of Covid-19 in March 2020, however, London’s tourism industry has had to withstand a 62% hit to spending, shouldering a £6.6bn shortfall compared to the previous year. As a result, the tourist accommodation industry has suffered greatly, with experts predicting that it will take at least 4 years to recover despite an optimistic uptick over the past summer. To add insult to injury, the British Tourist Board had only just celebrated its 50th anniversary a month before the first of the country’s lockdowns came in with a royal-attended ceremony—talk about bad timing. As many thousands of jobs in the sector disappeared thanks to the pandemic, the name “hotel” also took on a new, more contentious meaning as many sites once a facilitator for exciting city breaks and a relaxing getaways were transformed into the misery of a quarantine hotel, whose prison-like conditions hit the headlines across Britain.

But as the pandemic slowly (hopefully) ebbs and the hotel industry begins to make a comeback, there’s no better time to reflect on the significant impact hotels and their counterparts have made and continue to make on the urban fabric of London, and why they are important icons of a modern capital city.

Travel has always necessitated somewhere to rest up, whether it be at the destination or along the way. So developed the inn, the precursor to the contemporary hotel, to accommodate those travelling the bumpy pre-Industrial roads by horse, providing food, drink, stabling, and a place to sleep. These coaching inns quickly became a mainstay along Britain’s roads and were a necessary component of the country’s infrastructure for centuries, up until the Industrial Revolution. Chaucer described one such inn as the site from which his pilgrims departed in The Canterbury Tales:

“Bifel that in that season on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay…

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,…”

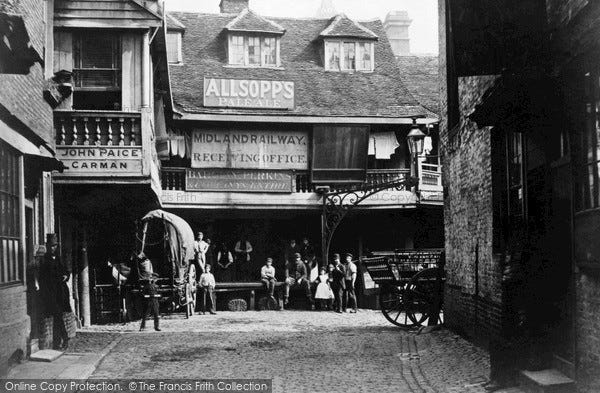

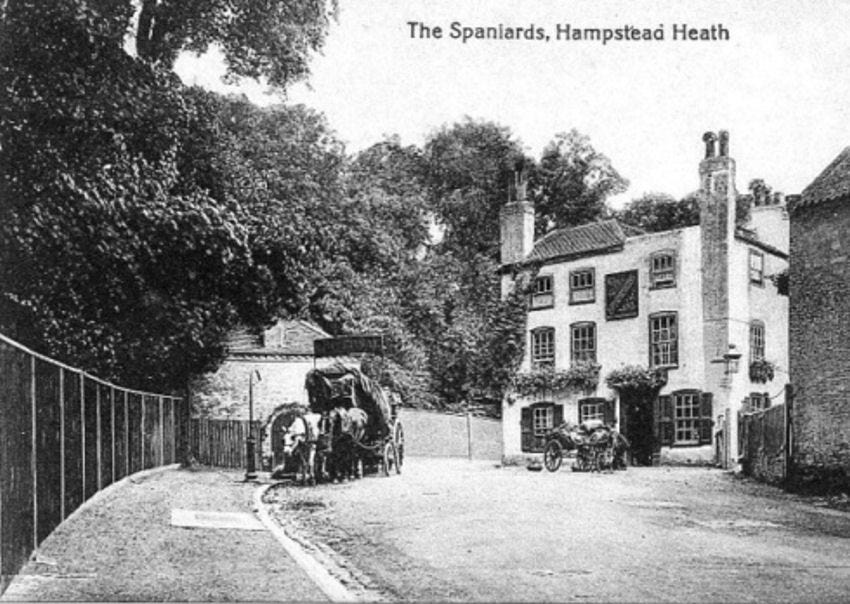

The Tabard was demolished in 1873, as were many like it, thanks to the rapid industrialisation of the 19th century. Some do still exist, generally in more rural parts of the country where long journeys by road are still commonplace, but they have long since replaced their stables with carparks. A handful survive in London too, such as the spectacular National Trust-owned George Inn in Borough, which was rebuilt in the 1670s following the Great Fire of London, and The Spaniards, which can be found straddling the border of Camden and Barnet. Built in 1585 and a regular haunt of the highwayman Dick Turpin whose father was supposedly the landlord, The Spaniards remains a truly unique spot for a pint.

But despite causing the decline of the coaching inn, industrialisation brought with it even more travellers to the increasingly vibrant cities via the new railways, and they too needed somewhere to stay. The capital’s lodging houses couldn’t cope with the influx of tourism, so enterprising businessmen began to build small hotels around the city, such as Claridge’s in Mayfair, which opened its doors in 1812. These quickly filled up too and were followed by grand hotels at railway termini, which not only housed high paying guests but also acted as a means of showing off the wealth and status of the new train companies. The Great Western at Paddington, the Grade I-listed Midland Grand at St. Pancras, The Grosvenor at Victoria, and many more were founded across the following few decades, most of whose rooms can still be rented.

Soon a tourist industry was booming and luxury hotels such as The Ritz, The Dorchester and The Royal Horseguards Hotel, which housed the office of MI6 chief Sir Mansfield Cumming (the alleged inspiration for 'M' from James Bond) were opened. Perhaps London’s most famous hotel, The Savoy, threw its doors open around this time as well, welcoming celebrity guests from Oscar Wilde to Winston Churchill—it also possesses the only road in the country where it is mandated that cars drive on the right.

Following the Second World War, international tourism, buoyed by advances in air travel, was all the rage, increasing the number of visitors from 1.6 million in 1963 to 6 million by 1974. Thus ensued the Hotel Development Incentive Scheme of 1976 that saw hundreds of hotels of all shapes and sizes built across the capital that catered to more than just the wealthy. Hotels in unused grand buildings and former offices that didn’t align with the trend towards more open plan workspaces opened apace and even more luxury sites were developed in newly upmarket neighbourhoods like Canary Wharf and West India Quay. Travelodges, Holiday Inns and other budget hotels became increasingly popular towards the end of the 20th century alongside cheap flights, and into the new millennium the building has only continued, helping London reach its current total of almost 150,000 hotel rooms.

For those who live near to a hotel, its presence can certainly be felt. Firstly, it is likely to indicate that the area is going to be affected by a portion of the population being transient in nature, which may mean an increase in demand for shared economy lettings such as Airbnb and Onefinestay. Additionally, those who are only temporarily staying in an area place little to no burden on community medical and educational infrastructure. However, they are unlikely to be long term community stakeholders, and so their presence may discourage the building or maintenance of such infrastructure, leading to a decline in important community spaces. Likewise, transient populations are less likely to be interested in partaking in long term community enhancement activities.

As mentioned above, probably the biggest impact of the hotel industry on Londoners is its provision of jobs. Hotels and hospitality more generally are a key component in maintaining the cultural diversity of London, not only in offering accommodation to overseas visitors, but also in offering opportunities for entrepreneurialism, and jobs to those who have moved from abroad—as C. Michael Hall and Jan Rath write, “it is hard to imagine urban tourism without immigrants.”

Historically, amenities would grow and cluster around a new hotel to make the most of the guaranteed and self-renewing customer base. Today, though, for smaller establishments the location of the facilities within a city has been considered crucial to where it will be built. When Ellsworth Statler, widely considered to be the father of the modern hotel industry, stated that the three most important factors in the success of a hotel are location, location and location, he uttered a truism that has yet to be disproven. The proximity of the accommodation facilities to London’s attractions, such as shopping and entertainment centres, restaurants and cultural resources, is considered by developers and investors as a necessary condition for success.

The underlying assumption behind this is that the typical tourist in need of hotel accommodation wants to exert as little effort as possible to reach a destination and therefore prefers staying in accommodation within walking distance of choice attractions. It’s unsurprising then that when new attractions arise or an area becomes trendy, a hotel or two is never far behind. Therefore, an entertainment business could do worse than having a hotel built near it. More recently, in order to maintain their viability, authorities have sought to redistribute hotels outside of London's centre but it will be sometime before conclusions can be drawn as to whether the suburbs can bear much hotel land use and maintain London's the attractiveness to its visitors.

So hotels really are part of London’s heritage, emerging out of the traditional coaching inn that kept travellers fed and watered, and developing thanks to the ever-prized public transport network that fed it, for which the city has become globally renowned. They remain icons of industry and adverts for a true international metropolis, providing a bed for all visitors from near or far, providing opportunities for entrepreneurs and jobs for Londoners old and new. As the tourism industry gets back on its feet, the impact of hotels and their customers, for good or ill, will be more profoundly felt on those who live and work nearby, and it’s for that reason that now more than ever we should take notice of these storied pieces of architecture that have allowed London to become the global capital it is today.