Ever since it developed as a city, London has been blighted by road traffic. Be it horses, carriages or cars, the city’s streets were always full to bursting, and measures have forever been implemented to try and curtail what’s become the worst congestion in Europe. One such recent course of action has been the Ultra Low Emission Zone, or ULEZ, whose boundaries are set to expand on Monday. To coincide with this new legislation, we thought we’d take a short trip through the history of urban traffic and attempts to control it, and see that clogged streets are not just a modern phenomenon!

For over 2,000 years, roads have enabled millions of city dwellers, traders and wanderers to move freely from city to city without having to immerse themselves in the unfamiliar and uncharted wilderness. It was the Romans who constructed the first roads, and as a result they were forced to introduce the first control mechanisms to quell the swelling traffic. Julius Caesar banned wheeled transport entering Rome during the day, and this was quickly expanded to other cities. Later, during the 1st century AD, Hadrian put limits on the number of carts that could access urban areas full stop.

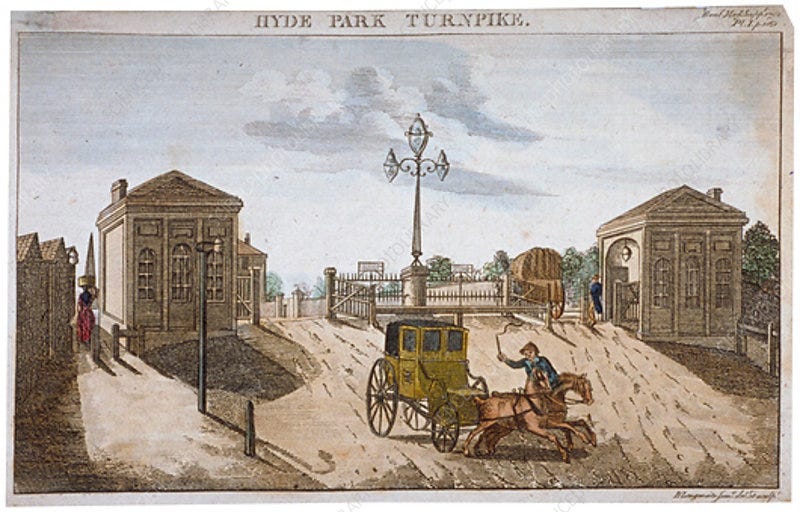

In England the Highways Act was introduced in 1555 under the reign of Mary I. This legislation ensured the maintenance of roads by those who used them and would have encouraged local authorities to implement restrictions on traffic in order to prevent any extra wear and thus extra upkeep. Parking preventions were commonplace throughout European cities from the 1600s, with many roads established as one-way systems. The country’s roads remained in a terrible state, however, making travel slow and painful, so turnpikes were introduced in the early-18th century, forcing travellers to pay a toll to use the roads that would be reinvested in their care.

As urban centres further developed and industrialised, their populations and the accompanying vehicles ballooned. Local traffic police were quickly drafted in to keep order, the first documented example of which was in 1722, decades before Fielding’s Bow Street Runners, and more than a century prior to the establishment of Robert Peel’s Met. This clearly demonstrates the urgent problems congestion was causing.

Traffic declined alongside the introduction of the railways and later the tram system, as visitors to the cities found them quicker, cheaper and more comfortable than the cobbles, confirming the long-held and still very relevant thesis that more public transport means less gridlock. But despite their initial success, the expansion of the trains couldn’t keep up with torrents of people flowing into urban centres, and technological advancements in personal transport were all the rage. Even the bike boom of the late-19th century couldn’t draw people out from their individual carriages.

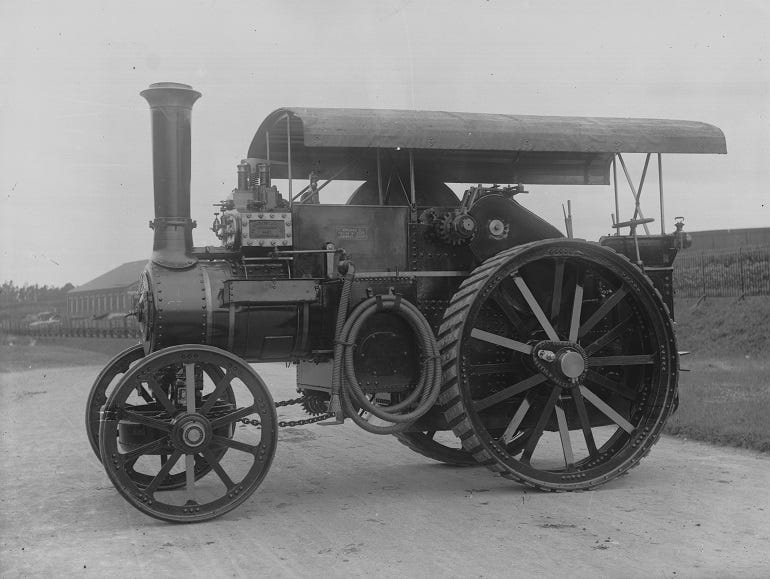

Steampunk-style traction engine-powered road locomotives that could only be operated by a three-man crew quickly arose from the furnaces of the Industrial Revolution. Though they may seem comical to contemporary passersby, these 12-tonne behemoths that bellowed steam and deafened passengers proved a significant threat to unsuspecting Victorians, so to reduce the threat of injury a speed limit of 10mph had to be introduced in 1861. This was later reduced further to 4mph in less urban areas and 2mph in city centres.

It was a railway engineer who pioneered the first physical traffic control though. J. P. Knight’s traffic light was inspired by his own railway signalling system, and was installed outside the Houses of Parliament in 1868 to prevent the build up of horse drawn carriages which forced pedestrians too walk too close to the politicians for comfort. The 6.7m tall pillar had semaphore arms that signalled stop and go, and, alongside red and green gas lamps, were controlled by a police constable. The system was generally a success, until it exploded in 1869 from a gas leak. Nonetheless it was adopted across London and was exported abroad, with many early-20th century examples found in the United States and France. Electricity and degrees of automation soon replaced gas and manpower, but the general traffic light mechanism remained, and indeed still remains practically the same to this day.

Development of the motorcar continued, becoming popular amongst the rich in the form of the Ford Model T, which was first produced in 1908. By 1930 horse-drawn transport was all but a thing of the past, replaced by almost 2.5 million petrol-powered cars. All speed limits for car traffic were removed in England in 1930, but were quickly reintroduced with a limit of 30mph in built up areas, even though the speedometer wasn’t made compulsory until 1937.

It wasn’t until after the Second World War though that the age of the car really took off with massive transformations to the road network. The government had taken control of road maintenance in 1936, but the 1949 Special Roads Act gave the Ministry of Transport license to construct roads that were not automatically rights of way. Huge lengths of motorway were built to divert car traffic from city centres, with the Preston Bypass the first to open in 1958. Car ownership skyrocketed now the roads were enjoyable to ride, and personal, individual modes of transport were no longer just aspirational but essential to travel between cities. Between the early-1950s to the mid-60s, household car ownership jumped from around 10 million to over 40 million, while at the same time the Chairman of British Rail, Dr. Richard Beeching, was closing over 4,000 miles of the country’s rail network in the notorious Beeching cuts.

By 1972, 1,000 miles of motorway had been opened to much protest from environmental campaigners and those who had lived in their paths, but what was intended to relieve pressure on the country’s roads in fact only encouraged more and more people to purchase cars and manufacturers to produce them, and, due to repressed demand, traffic soon grew to fill every new road that was constructed. It turns out that making it easier for people to drive will encourage more people to do so! Though this was the intention of the government, the frustrations of motorists forced to sit in polluting and noisy congestion they themselves were part of caused problems for those in charge. In response, the government at the time sought to implement a predict and provide policy, in which it set out to project traffic areas and battle congestion through targeted extensions of the road network.

This idea of "building our way out" of urban traffic congestion problems has for a long time been decisively rejected by both the transportation community and the public at large. It’s widely accepted that building more or larger roads does nothing to quell vehicle traffic; in fact, it increases it through the phenomena of ‘induced traffic’. This is due to a variety of mechanisms by which adding roads can generate new traffic, such as encouraging more unnecessary trips, making it easier to travel long distances by car, and inducing a modal shift from more public and communal forms of transit.

During the 1980s, the low fuel costs and Thatcher’s pro-car policy caused a further boom in the transport sector which pushed for an increase in road vehicles by over 140%. The government response proved to be ineffective as the addition of new routes and the extension of the existing ones didn't manage to reduce the congestion levels, despite a 24,000-mile road expansion between 1985 and 1995, and motorways totalling 2,000 miles by 1996. During this period road traffic increased by 80%, but only 10% of the capacity to accommodate it was developed.

The "Agenda 21", "Our Common Future" report and the EU Transport White Paper, underlined the need for traffic reduction strategies as a method to preserve the environment. To that end, in early 2003, the London's Congestion Charge scheme took effect, temporarily curbing traffic levels in London. However, as congestion levels are once again on the rise, transport planning officials call for more traffic data to be collected and used to guide targeted road design alterations, and managing the direction, frequency and intensity of vehicle movement. Although congestion charges managed to temporarily lower traffic levels, they’re firmly on the rise once again causing inner London travel time to increase by around 50% over the optimum.

More recently in 2019, the Congestion Charge Zone has expanded into the Ultra Low Emissions Zone, and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods have controversially been implemented by many boroughs. But despite all these attempts to quell congestion, it’s been found that to this day Londoners lose about 80-100 hours annually sitting in traffic.

So where do we go from here? We’ve seen that decades of poor planning and extra roadbuilding does little to stop the build up of congestion, in fact it does the very opposite. In spite of this, more and more roads continue to be built with the promise of reducing traffic or pollution in one area, even though in reality it is exacerbating the problem, or at best (though increasingly rarely) simply moving it somewhere else.

It is likely then, that only a huge overhaul of the country’s transport system through massive expansion of and investment in public transport networks, and harsher sanctions on driving on the road will be able to reduce the Britons’ reliance on the motorcar. Beyond the controversial HS2 project and the aforementioned expansion of London’s ULEZ, there seems to be little attempt to provide this change. So for now, it’s probably best to invest in a comfy car seat and find some decent podcasts as the rush hour tailbacks are, like a held-up motorist, going nowhere fast…